|

Revisiting the Jihad of the Companions

after the Demise of Prophet Muhammad (sws)

Prologue

According to Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī, the guidance of the

Almighty in the era of messengers works on the basis of the concept of itmām al-hujjah.

Itmām al-hujjah means communication of the truth to the extent that that no

excuses remain for the addressees. When itmām al-hujjah is done on a group of

people, they can no longer claim that they genuinely did not become convinced by

the message of truth. After itmām al-hujjah the only reason that a person may

reject the truth will be his own arrogance. Itmām al-hujjah is the basis of

worldly reward and worldly punishment of the believers and rejecters who have

been the direct addressees of a messenger of God. For these groups the worldly

reward or punishment continues into the Hereafter. According to Ghāmidī, the

offensives launched by the companions on the neighbouring countries after the

demise of the Prophet (sws) was on the basis of itmām al-hujjah. These were the

same countries whose rulers were sent warning letters by Prophet Muhammad (sws).

The mechanism of how itmām al-hujjah applies to these countries, as understood

by Ghāmidī, is a complex one. This article is the outcome of series of detailed

discussions with Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī and aims to reflect his views on this

important subject.

The article ends with my reflections on the subject.

The article has been written for a reader who is already

familiar with the concept of itmām al-hujjah and its consequences as explained

by Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī. A brief reminder is given at the start of this article.

For the sake of brevity throughout the rest of this article I will use Ghāmidī

to refer to Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī.

Itmām al-Hujjah and Daynūnah

وَ لِكُلِّ أُمَّةٍ رَسُولٌ فَإِذا جاءَ رَسُولُهُمْ قُضِيَ

بَيْنَهُمْ بِالْقِسْطِ وَ هُمْ لا يُظْلَمُون (١٠:

٤٧)

And for each community,

there is a messenger. Then when their messenger comes, judgement will take place

among them with justice and they are not wronged. (10:47)

The above verse is about one of the most important Sunan

(ways) of the Almighty which in the words of Imām Hamīd al-Din Farāhī can be

referred to as daynūnah. Daynūnah (from dayn in Arabic, meaning retribution) in

its general meaning refers to the system of rewards and punishments of the

Almighty that is fully manifested on the day of judgement. Daynūnah in its

specific meaning, as Ghāmidī puts it, refers to the miniature day of judgement

that takes place in this world for the direct addressees of a messenger of God.

It may thus be noted that the daynūnah is the consequence of itmām al-hujjah.

In the words of Ghāmidī:

By this phase (i.e. itmām

al-hujjah), the truth has become so evident to the addressees that they do not

have any excuse except stubbornness to deny it. In religious parlance, this is

called itmām al-hujjah. Obviously, in it besides the style adopted and the

arguments presented, the very person of the rasūl plays a role in achieving this

end. The stage is reached that the matter becomes as evident as the sun shining

in the open sky. Consequently, at this instance, a rasūl to a great extent

communicates the fate of the addressees to them, and his preaching takes the

trenchant form of a final warning.”

Once the itmām al-hujjah takes

place, daynūnah of the addressees of the messenger starts. From the time of

Prophet Abraham (sws) onwards, this daynūnah has had two dimensions:

- Internal: This

refers to the reward that the believers and the followers of the messenger

receive in this world. This reward is mainly in the form of political strength

and domination over other politically associated nations. This reward continues

as long as they obey the religion of the Almighty. If they break the covenant

that they made with their Lord then their reward will cease and will be replaced

with humiliation, hardship and subservience to other nations.

- External: This

refers to the punishment of the rejecters during the era of the messenger. Those

rejecters that are polytheists are executed or perish at the hands of the

followers of the messenger or by natural calamities. Those rejecters that are

originally monotheist become subservient to the believers. Obviously the

internal dimension of daynūnah relates and contributes to the external

dimension. This external dimension of daynūnah also applied to the nations

before prophet Abraham (sws).

Ghāmidī has described five phases for the process of itmām

al-hujjah and daynūnah in his book Mīzān..

However in order to better understand the relationship between daynūnah and

itmām al-hujjah, in this particular discussion, Ghāmidī breaks up the process of

itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah into three phases as follows:

Phase one: General Da‘wah (preaching)

In this phase, the messenger starts giving da‘wah

(preaching) and indhār (warning) to mainly the leaders but also to the people of

the nation that he is addressing. The indhār is to let the addressees know the

consequences if they arrogantly reject the messenger and his message. One of the

instrumental tools for warning the nations at this phase is to remind them of

the destiny of those nations before them who had been warned by their messengers

and had been punished and who perished as a result of their arrogant rejection

of the truth.

Phase two: Implementation of Daynūnah for the Leaders

Following da‘wah and indhār, once the phase of itmām al-hujjah

is concluded for the leaders of the nation, the punishment of these leaders

starts. This is more specifically true when the divine punishment was carried

out by a messenger and his immediate followers. In other cases, as described in

the Qur’ān, phase two and phase three were practically merged together as one

phase and the divine punishment appeared in the form of a natural calamity.

Phase three: Ultimatum to the Common Masses

This phase according to Ghāmidī is the natural consequence

of the previous two phases and happens inevitably after them. The punishment of

the leaders of the nation contributes towards itmām al-hujjah for the common

masses and therefore an ultimatum is given to them that unless they let go of

their arrogance and submit to the truth, they too will face the same or a

similar punishment as their leaders. Phase three ends with implementation of the

ultimatum.

It is important to note that like a chain reaction, phase

three is simply the consequence of phases one and two. In other words, just as

the destiny of the nations who were punished in the past serves as a concrete

evidence of the truth for the leaders of the addressed nation, the punishment of

these leaders (along with the punishment of the past nations) serves as a strong

evidence of the truth for the common masses of the addressed nation.

To be more specific about the era of the prophet (sws), the

application of the above three phases to his time is as follows:

Phase one: The Prophet (sws) started indhār-i ‘ām (general

warning and preaching) after a short period of private preaching to his friends

and trusted ones. Sūrah Muddaththir can be seen as the beginning of this general

warning and preaching for the Quraysh. While this warning was towards all the

Quraysh (and in fact all who could hear and understand it at the time) it was

specifically focusing on the leaders of the Quraysh. Many of the chapters of the

29th and 30th sections (juzw) of the Qur’ān (that is the seventh group of

chapters of the Qur’an in the thematic sense)

are specifically warning the leaders of the Quraysh. One of the means of warning

was to remind the Quraysh about the destiny of the nations before them who like

them, were among the direct addressees of messengers and met their punishment or

were rewarded in this world. The stories of these nations were considered as

historical facts by the Quraysh or the people of the book in the Arabian

Peninsula. In particular the Quraysh had a clear historical memory of what

happened to the people of Thamūd and ‘Ād.

Phase two: The punishment of the leaders of the Quraysh

started by their defeat in the battle of Badr and their subsequent defeats and

retreats after that. During these battles a number of chief heads of Quraysh

where either killed or humiliated.

Phase three: The defeat and humiliation of the leaders of

the Quraysh naturally and automatically served as further proof for the truth of

the Prophet’s (sws) message and therefore further contributed in warning the

common masses of the Quraysh. This warning reached its culmination at the time

of the invasion of Makkah, as described in Sūrah Tawbah. The defeat and

humiliation of the Quraysh itself served as a proof of the truth for the rest of

the Arabs in the peninsula.

Elaboration of the Mechanism of Itmām al-Hujjah

Before proceeding to the itmām al-hujjah after the demise

of the Prophet (sws), it is helpful to describe and illustrate some of the

details of the above process as explained by Ghamidi:

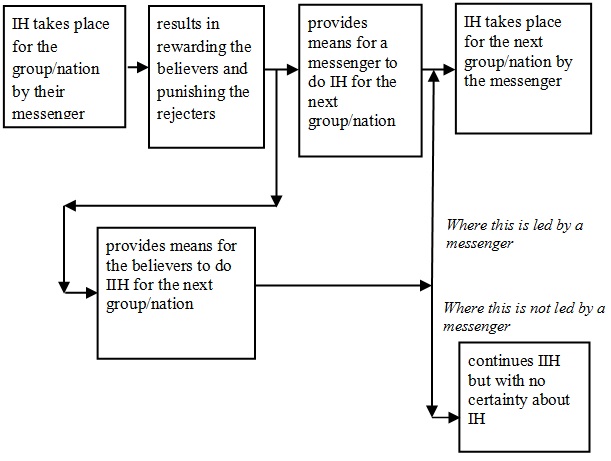

Itmām al-hujjah works in a chain reaction. In this chain

reaction, God provides the required means. One of the main means is the reward

and the punishment of a previous group/nation to whom a messenger was sent.

Witnessing or hearing the news of the past punishments or rewards serves as a

means for the next group/nation. A messenger of God (and if applies, his

followers) will use this means for itmām al-hujjah. However, as for the

followers, all they can do and all that they are responsible for is putting

their efforts to strive for itmām al-hujjah. In the words of Ghāmidī, this

endeavour and effort can be translated as ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah in Arabic

(literally meaning to strive for itmām al-hujjah). Ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah by

the believers may or may not result in the actual itmām al-hujjah and in the

absence of any divine indications there will be no way to establish whether the

actual itmām al-hujjah took place. However a messenger of God completes the

actual itmām al-hujjah with the direct support of the Almighty. Once itmām al-hujjah

happens for the new group/nation and the reward and punishment takes place for

them, again this reward and punishment is used as means for ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah

by the believers for the next group/nation, and as means for actual itmām al-hujjah

where a messenger is also sent to that group/nation. This mechanism of the chain

of itmām al-hujjah can be illustrated as follows:

Figure 1: Chain of itmām al-hujjah as described by Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī

Note:IH: itmām al-hujjah; IIH: ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah

As described earlier, in the above chain of events, where

applicable, the itmām al-hujjah and punishment of thse leaders of a nation

precedes the itmām al-hujjah and punishment of the nation. One of the other

important points that needs to be emphasized in the above figure is the division

of responsibilities between a messenger, his companions (from among the chosen

nation) and the rest of the chosen nation (ie. from the generation of the

companions). This is further clarified by the following table:

|

Phase

|

Responsibility

|

|

Messenger |

Companions from among the chosen nation |

Chosen Nation (other than the companions) |

|

Ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah |

Not Applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

|

itmām al-hujjah |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Implementing the Punishment |

where applies |

where applies |

No |

Table 1: The dividing of responsibilities of events in the

process of itmām al-hujjah, as explained by Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī

As it is clear from the above table, it is only the

companions (immediate followers) of a messenger that may be allowed to implement

the punishment after the messenger has done itmām al-hujjah. The next

generations of the believers do not have that permission and responsibility. The

expression “where applies” in Table 1 refers to the information given in the

Qur’ān about the ways of punishing the previous nations. Ghāmidī explains in

Mīzān:

At times, this punishment

is through earthquakes, cyclones and other calamities and disasters, while, at

others, it emanates from the swords of the believers.

According to Ghāmidī, the

position of a nation being appointed as witness (shahādah) to the truth, as

mentioned in the Qur’ān (2:143; 22:78), is in fact the authority of that nation

to do ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah.

Application of the above after the Demise of the Prophet (sws)

Ghāmidī explains that exactly the same process was adopted

for the countries that were invaded by the companions after the demise of the

Prophet (sws). These were the same nations to which the Prophet (sws) sent

letters of warning. The companions, through their ijtihād (deduction),

considered it their responsibility to do their duty with this regard just as

they fulfilled their duty with regard to the direct addressees of the warnings

of the Qur’an (i.e. Quraysh and the People of the Book in the Arabian

Peninsula).

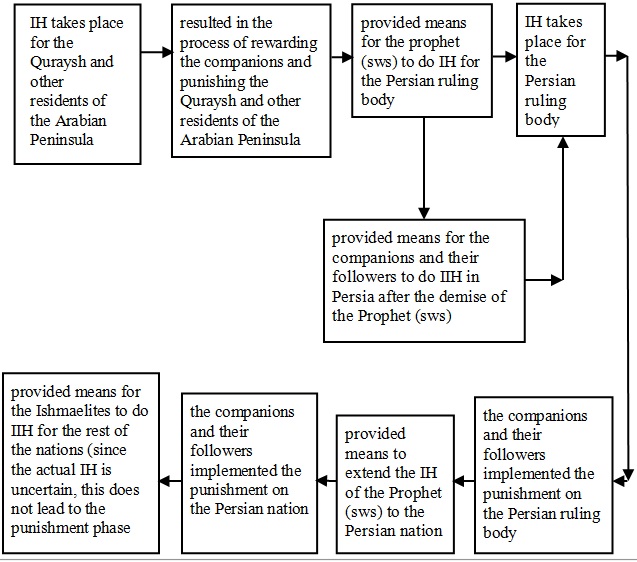

This similar process of itmām al-hujjah after the demise of the Prophet (sws) is

explained in the following section. To illustrate this better, Persia is

referred to as an example where the following had a full application according

to Ghamidi:

Phase One: The victories of Muslims, along with the general

knowledge of reward and punishment of nations which existed before, provided the

means for itmām al-hujjah by the Prophet (sws). The Prophet (sws) initiated

itmām al-hujjah by sending letters to Khusrū Parvayz the then king of Persia.

The letters warned the king to accept the message of Islam and informed him that

his country will fall apart if he (the ruling body) does not accept the message

of truth. Although the letters were literally addressing the king of Persia,

they were in fact addressing the ruling body of Persia. As the king of a

powerful country at the time, Khusrū Parvayz and his ruling body were aware of

the developments in Arabia. They were later aware of the fact that the leaders

of Quraysh were defeated and that the whole Arabia was dominated by Muslims.

They were also aware of some of the stories of the nations before them who were

punished due to rejecting the messengers of God. All this provided them with a

clear opportunity to realize and appreciate the message of truth and as a

consequence they were subjected to itmām al-hujjah. As history reveals, the

warning was not taken seriously by Khusru Parviz or the later kings of Persia

and their ruling bodies.

Phase two: The companions were aware of the history of some

of the nations who witnessed itmām al-hujjah before them. They had obviously

heard the directives and warnings in the Qur’ān related to the concept. They

themselves were the direct addressees of some of these directives and they knew

and had practically witnessed their own role in this regard. They were therefore

fully aware of the concept of itmām al-hujjah and its implications. They then

witnessed the sending of letters by the Prophet (sws) and noticed the contents

of the letters where (in case of Persia) the falling apart of the country was

predicted. They therefore concluded through their ijtihād that the law of itmām

al-hujjah is also applying to and is in fact in process for these nations,

including Persia. They also had the means of ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah provided

to them. Accordingly they first carried out their responsibility of punishing

the ruling body of Persians. The Persian nation witnessed how against all odds,

a powerful empire fell down apparently at the hands of much less powerful and

less skilful army of Arab Muslims. What once was seen as one of the two super

powers of the time was defeated by a nation that was not even considered as a

serious rival in the region.

Phase three: The defeat of the then king of Persia and his

ruling body provided further means for ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah for the

Persian nation. Ghāmidī asserts that the Persian nation overall were aware of

the letters of the Prophet (sws) to their leadership and were also aware of the

Prophet’s (sws) prediction of Persia falling apart if they did not submit to the

truth. In this way, the letters of the Prophet (sws) initiated a process that

eventually reached itmām al-hujjah for the Persian nation as well. As explained

earlier, according to Ghāmidī this third phase takes place naturally after the

first two phases. It is therefore correct to say that the itmām al-hujjah for

the entire Persia was the work of no one but the Prophet (sws) himself

(supported and blessed by the Almighty of course).

In the above mechanism of itmām al-hujjah for Persians, the

letters of the Prophet (sws) should be seen as an instrumental tool that served

as a leading sign. While the ruling body of Persians and through them the

Persian nation were warned by these letters, the companions considered them as

indirect instructions to implement the punishment on Persia if they do not

submit after itmām al-hujjah. Not only this, the companions also considered the

contents of the letters to be a clear indication and a divine information that

the process of itmām al-hujjah is taking place and will be competed for the

Persian ruling body and the Persian nation. As explained above, this

understanding was backed by their full awareness of the law of itmām al-hujjah

for which they themselves played a key role in the Arabian Peninsula. As stated

before, the letters contained predictions of Persia falling apart if they did

not submit to the message of truth. The ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah by the Muslim

army in Persia should be seen as the offshoot of the process of itmām al-hujjah

that was started by the Prophet (sws). Accordingly the Muslim army subjected the

Persian nation (on a gradual scheme) to the law of punishment of people of the

book after itmām al-hujjah, that is, becoming subservient to the chosen nation

by paying jizyah.

The above is illustrated in the following figure. Figure 2

is in fact application and elaboration of figure 1 for Persia after the demise

of the Prophet (sws):

Figure 2: Application of the chain of Itmām al-Hujjah on

Persia after the demise of the prophet (sws), as described by Jāved Ahmad

Ghāmidī

Note:IH: itmām al-hujjah; IIH: ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah

Ghāmidī explains that while the source of events related to

itmām al-hujjah for the Arab nation is the Qur’ān, the source of the events

related to itmām al-hujjah for Persians is history. He explains that the history

of invasions of Muslims after the demise of the Prophet (sws) has never been

looked at from the itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah point of view. Ghāmidī is of the

view that if the history of these invasions were looked at from this standing

point then many supporting evidences for the above explanation could have been

derived. He has noted these supporting evidences himself and is keen for his

students and other scholars to study and document them through research.

Summary of the main points

A few important points that can be derived from the above

explanation are singled out and emphasized here. I intend to avoid the risk that

the reader may not notice these very crucial points in the above rather long

writing:

1. The attack of the companions to Persia and other

countries were motivated by their ijtihād after observing the letters of the

Prophet (sws) to those countries. The companions on their own ijtihād concluded

that they were responsible to implement the due punishment, after itmām al-hujjah

on these countries had been done by the Prophet’s (sws) initiative.

2. It was not the companions or the Muslim army that

completed itmām al-hujjah for the Persian rulers. It was in fact the Prophet (sws)

that did it.

3. Ghāmidī is not claiming that the letters of the

Prophet (sws) were enough to do itmām al-hujjah for the Persian rulers. The

letters were in fact part of a system of means that are always available for

messengers when they do itmām al-hujjah. This system included the news of the

past punished and rewarded nations as well as those in the Arabian Peninsula at

the time of the Prophet (sws).

4. Following from the above point, in the words of

Ghāmidī, there is no difference between the Prophet’s letters to the heads of

the countries and his talks with the heads of Quraysh. Both these were supported

by the evidences of punishment after itmām al-hujjah and it was together with

these evidences that these letters or those talks contributed in itmām al-hujjah

for the heads of the countries and the heads of Quraysh.

5. Similarly it was not the companions or the Muslim

army who completed itmām al-hujjah on Persia or the other countries. Itmām al-hujjah

for these countries was a natural and “automatic” consequence of observing the

destiny of their ruling bodies.

6. The companions and the chosen nation of God were

not responsible for itmām al-hujjah, they were not necessarily capable of itmām

al-hujjah and did not even know on their own, whether itmām al-hujjah was done

for a group or a nation. As the intermediate nation who had been given the

position of shahādah (being witness of the truth for others) they were and they

are only responsible to do ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah. From among the chosen

nation, only the companions had the extra responsibility of implementing God’s

punishment on nations for whom itmām al-hujjah had been done.

7. The companions knew that itmām al-hujjah was taking

place for the Persian rulers and Persian people because the letters of the

Prophet (sws) had promised punishment of Persia in case they did not accept the

Prophet’s (sws) invitation to the message of Islam. Since the Persian rulers

rejected the message of Islam the companions concluded that the perdition of the

Prophet (sws) would then materialize, which indicated to them that itmām al-hujjah

was done for the rulers and was naturally going to be applied to the Persian

people as well.

8. Ghāmidī believes that history shows that the

punishment that was carried out by the companions in Persia (and other places)

was implemented based on the principles of itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah.

However, since the companions were not directly guided by the Almighty or His

Messenger (sws) in this endeavour, Ghāmidī does not rule out the possibility

that there could be mistakes and errors happening occasionally as well.

9. Although Ghāmidī derives the principles of itmām

al-hujjah and daynūnah and their implementation in the Arabian Peninsula from

the Qur’ān, he does not claim that the details of application of these

principles in Persia and other countries are also mentioned in the Qur’ān. He

appreciates that the only source of reading about the application of these

principles in these countries is history.

Author’s Reflections and Thoughts

I would like to end this article with some final personal

reflections on the subject. My main problem with the idea of applying the

principle of itmām al-hujjah on Persia and other countries was that at times I

felt that in our keenness to uphold the principles of itmām al-hujjah, we

sometimes seemed to unconsciously try to rewrite the history of these invasions

in order to make them fit with these principles. I could not help but notice

some not very impressive stories about some of the things that happened during

these invasions. Although I had not studied the reliability of these reports, I

found it not very academic and not quite objective to dismiss these reports only

because they were not in line with the principles of itmām al-hujjah. All this

however was based on indirect narratives of Javed Ahmad Ghāmidī’s thought that I

was exposed to and not based on direct discussion with him.

Throughout the long sessions of discussing this subject

with Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī I pleasantly found my mind at peace. The assertion of

Ghāmidī that the companions acted on their own ijtihād solved conflicting points

in my mind. This simply means that from an academic point of view, we should not

worry about reports of unjustified acts at the time of invasion of these

countries. If we do find reliable reports of some acts that were not in line

with the principles of itmām al-hujjah, then this does not question those

principles. These reports of unjustified acts and practices, if proved reliable,

are simply showing the fact that the army of Muslims, in the absence of direct

leadership of the Prophet (sws), was not benefitting from a direct divine

supervision and was therefore prone to errors, mistakes and mishandling of

affairs. In fact even when the prophet (sws) was supervising the battles at his

time, some mistakes of the Muslim army that were out of his control and

observation would take place. It is only natural that in his absence more

mistakes and unacceptable deeds may take place during the extra ordinary war

situation.

This notion of the invasions being on the basis of ijtihād,

answers many questions, at least in my mind. Questions like how the companions

knew how far to go and how they decided when punishment was applicable to a

particular city or group of people, are all easily answerable by the concept of

ijtihād, which denotes that the companions (and under their leadership, the

Muslim army) did what to the best of their understanding was correct.

However, in my view, there are still a couple of inquiries

that need further discussion and elaboration. One relates to the Qur’ān and the

other one is about the practicality of itmām al-hujjah for some of these

neighbouring countries. I am not raising these points as criticisms. I refer to

these points as questions that demand further research and clarification:

The silence of the Qur’ān about the destiny of the

neighbouring countries in my understanding is a challenging point. In the Qur’ān,

we do not see any directives or any news about these countries (in the era after

the Prophet (sws)). The directives of the Qur’ān to the Prophet (sws) and its

warnings all appear to be limited to the Arabian Peninsula. On the other hand, I

can also understand and consider the potential argument that the Qur’ān does not

need to include directives about the application of the rule of itmām al-hujjah

on other nations, which is supposed to take place after the demise of the

Prophet (sws). It is worth listing all the verses that directly relate to itmām

al-hujjah and to study which ones are specific to the Arabian Peninsula and

which ones can bee generalized to other nations.

The second point is on the practical possibility of

completing itmām al-hujjah for the neighbouring countries. This is a point that

needs detailed historical research. The students of Javed Ahmad Ghamidi

(including myself) need to arrange for research projects to carefully review the

history of the companions and the neighbouring countries after the demise of the

Prophet (sws). The aim of such research will be to establish a number of facts

or nearly certain facts about the controversial era of history pertaining to the

attacks of the Muslim army to these countries. A number of questions may be

answered through these research projects, including, how did the companions

begin to decide about attacking those countries; what does history say about

their motives and purpose for these attacks; how consistent was the attitude of

the army of Muslims towards the people who they attacked; to what extent were

the heads of the states of these countries as well as the general public aware

of the developments in the Arabian Peninsula given that some of these nations

were not associated with Abrahamic religions to what extent were they aware of

the concept of daynūnah; people in most of these countries could not understand

Arabic, how was this obstacle overcome; what was the speed of spreading of news

in the era where no modern media and technology were in place; to what extent

were the general public in these countries aware of the letters of the Prophet (sws)

to their leaders, their contents and the response of their leaders to these

letters; what versions of the narrated contents of the Prophet’s (sws) letters

are reliable and what do they say; are there any evidences that the perception

of the Persians (for example) about the invasion of their country by Muslims was

any different from their perception of the past invasions by other armies (like

the Alexander’s army); when and how jizyah was applied to the residents of some

of the invaded countries and to what extent were they encouraged to become

Muslims rather than being punished by paying jizyah; how and through what

processes the residents of these countries gradually became Muslims.

Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī believes that when the history of these

events is read from the standing point of itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah then

things start to make better sense and more evidences will emerge in support of

these principles. It is interesting to see what parts of the history of that era

may match these principles and what parts may not match them.

However, since the understanding is that these invasions

were on the basis of ijtihād of the companions, no historical report will be

able to question the very principles of itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah. These

principles and their applications up to the demise of the Prophet (sws), as

skillfully and comprehensively explained by Ghāmidī, are clearly mentioned in

the Qur’ān. In fact “clearly mentioned” is an understatement. The whole theme of

the Qur’an and the whole thematic evolution of the Qur’ān are on the basis of

these principles. Whether the companions, in the absence of the Prophet (sws),

intended and managed to successfully adopt and apply all these principles in

detail is only a historical inquiry that does not change our understanding of

the principles themselves.

I personally believe that in this context it is also

important to consider another aspect of the concept of daynūnah, that is the

reward of the believers. I think (and I believe that this is what Ghamidi also

agrees with) that the invasion of the other countries was not just about

punishing those countries, but was also about rewarding the believers and the

new believers that would emerge from those countries. In my personal opinion,

even without itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah taking place, still those countries

were supposed to become part of the Islamic territory at the time to fulfill the

promise of rewarding the believers. In fact from purely political point of view

this promise needed to be fulfilled anyway. History shows that when a nation

starts to prosper in an extra ordinary way it needs more political dominance in

the world. In our time, this political dominance can easily take place by the

use of media and online technology as well as modern cultural symbols and tools.

However, in the past much of this political dominance could only take place by

physical, geographical dominance, i.e. invasion. In my understanding, the

promise of reward for the believers matched very well with the political

requirements of a fast growing nation of Islam at the time.

At the end, I would like to add that another thing I

learned through my interviews with Jāved Ahmad Ghāmidī was that it was possible

to be a very knowledgeable and formidable scholar and at the same time to remain

open minded, research oriented and humble in discussing Islamic issues. His eyes

were even shinier when I was bluntly and insistently questioning his whole

reasoning. For me, this point was even more educational than the whole

discussion on itmām al-hujjah and daynūnah:

نه هر

که چهره برافروخت دلبری داند نه هر که آینه سازد سکندری

داند

غلام همت آن رند عافیت

سوزم که در گدا صفتی کیمیاگری داند

هزار نکته باریک تر ز مو

اینجاست نه هر که سر بتراشد قلندری داند

Glossary

Itmām al-hujjah: Refers to communication of the truth to

the extent that no excuse remains of the addressees.

Ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah: Refers to the efforts to strive

for itmām al-hujjah.

Daynūnah: God’s reward and punishment that applies to the

direct addressees of His messengers.

Means of ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah and itmām al-hujjah:

This refers to exposing the rewards and punishments of previous group/nations

for a present group/nation.

Chain reaction of itmām al-hujjah: Refers to the fact that

itmām al-hujjah for a group/nation and its consequent rewards and punishments

serve as means to do itmām al-hujjah for another group/nation.

Shahādah (position of the messengers): Refers to their

responsibility of doing itmām al-hujjah and consequently judging among their

addressees.

Shahādah (position of the chosen nations): Refers to their

responsibility of doing ihtimām bi itmām al-hujjah.

_______________

|